Disco and Techno are Boring

Give it a rest guys

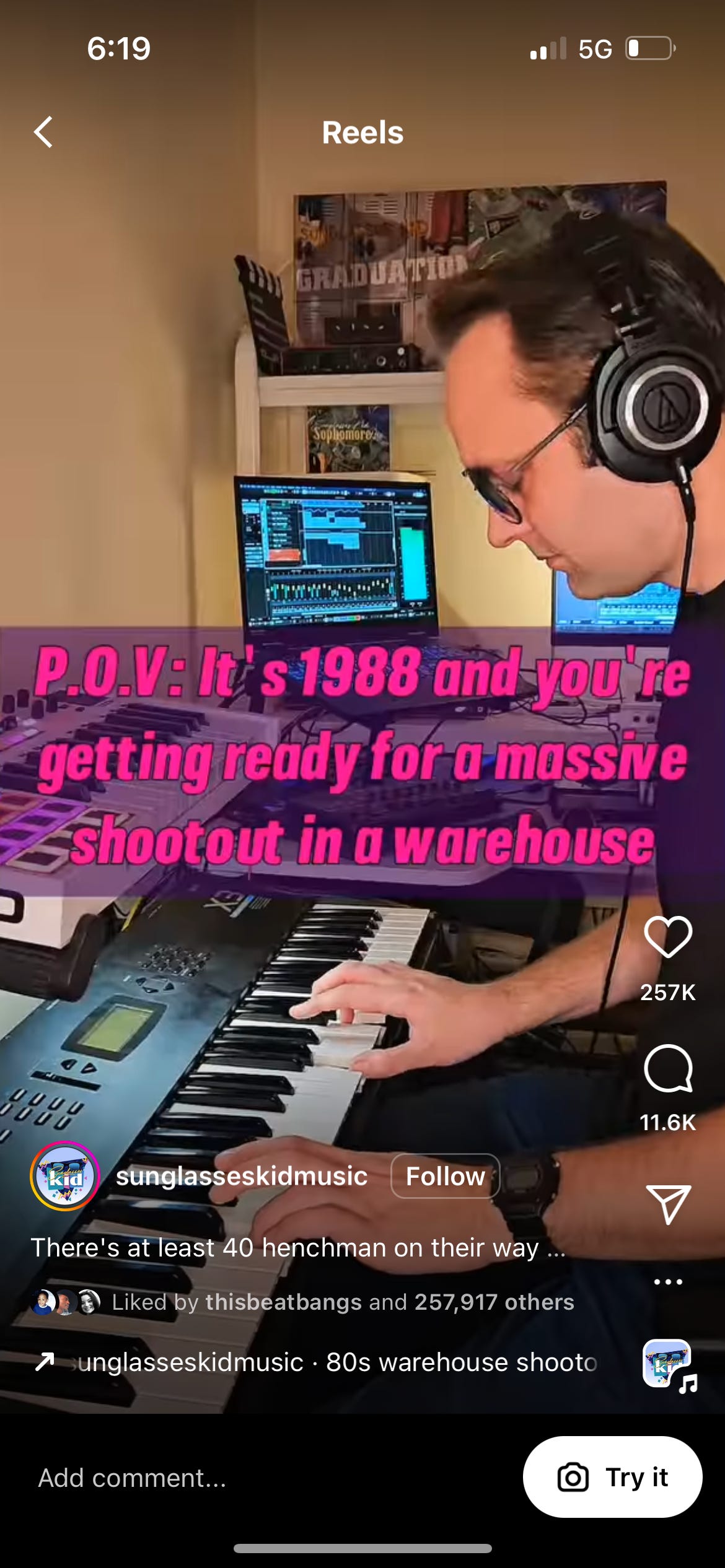

Above: a shard of sensation from the past resurfaces in a viral video momentarily inspiring an underserved audience

Disco and techno, as meaningful ideological and creative lanes, are rapidly being drained of contemporary significance, their aesthetic particularities increasingly numb to the touch. Do I like disco and techno? *Answering quickly* of course I do—as a specific musical-historical period which shaped my present reality and social world, absolutely. As a collection of sensuous affects which immeasurably broadened my awareness of what it means to experience life on earth, for sure. As a sources of an incalculable number of great songs, 100%.

But as a gesture which demands our attention, which could imply greater creative consequence, inherit political, cultural, or social meaning in the present day? Disco and techno alike are, quite ironically, prestige-magnets at a time when both genres are beginning to retreat from their longstanding status as the primary meta-genres which host each emergent trend within their own rhythmic and cultural matrix. The potency, centrality, and creative force as contemporary gestures they held for decades, as the main formal frameworks for modern dance music, either feel a little tired, or are already beginning to fade.

Not to down anyone doing good creative work, in whichever tradition they choose to market it. Likewise, I’m not against artists working within a creative lineage. Nonetheless, I would advise even the most vocal adherents to aesthetic and ideological apprenticeship in the creation of art, to reconsider their allegiance to genre—particularly genres of shrinking creative utility. I contend disco and techno have ceased to bear the same power, particularly when applied to contemporary listeners, whether listening to music old or new.

The post-Napster mp3 boom opened up a more egalitarian era for those interested in underground dance music. Now able to pierce the mysterious hierarchies based around the expense of vinyl records and scarcity, mp3s opened up dance music to a wider audience than ever before. Two decades later, the streaming boom accelerated these democratic impulses to a leveling extreme, revealing so much of what was lost—as curators, DJs, writers, and general creatives who could imbue a sense of narrative purpose to an obscure artistic phenomena were washed away in favor of a kind of social free-for-all, everyone empowered as a music expert recommending songs to his five or six friends. After an initially-exciting period in which the arrival of “DSPs” boosted unexpected, even egalitarian randomness, the music industry quickly gamed the new system and things became more formatted, a return to similar structures and strictures of traditional radio. One of the newer side effects of a more user-driven system—‘Spotify skip rates’—was that artists who essentially remade the same song over and over with slight variation could benefit. This new venue for enhanced exposure had some downstream effects that really hit around 2020, when everyone was sitting around at home and wanting to hear a song that sounded like a song they already liked, but a little different.

People loved this. They were tired of ‘gatekeepers,’ curators at every level—radio, labels, DJs, their friend who bought more records—and how they withheld access to music. In response, they embraced the opportunity to have a highly individuated relationship with broadly popular art, across genre. One could suggest Griselda, for example, benefit from this ecosystem, where playlists demand a constant influx of “new” songs in easily defined, familiar, and beloved styles. (“New” as a privileged category is itself problematic. More in a moment.) Artists who had a tendency to innovate or perpetually remake their sound—within or without creative traditions—were buried in the streaming deluge.

Unlike Griselda, who faced some mild criticism from the early stages for making comfort food rap for millennial dads, “nu disco” has had an under-criticized role supplying the market with mid. In 2020 alone—a year in which clubbing was somewhat curtailed—we were greeted with acclaimed albums like Jessie Ware’s What’s Your Pleasure?, Roisin Murphy’s Roisin Machine, Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia, Kylie Minogue’s Disco…And these are just the tip-of-the-iceberg prestige selections, the well-executed versions of a broader aesthetic glut. (Whether you consider well-executed to be high praise we can take on a case-by-case basis.) I would never argue that we should halt all production of disco, although maybe we should until we figure out what’s going on, but certainly one gets the impression that the nu-disco playlist has become a privileged cultural format, despite rapidly becoming a bottomless well of flattened cliches.

“But” you sputter, “disco and techno do have variety and range!” Well exactly—disco as a historic period is as creatively wide-ranging as any genre created; in the Loft, David Mancuso incorporated global music with a breadth of grooves and styles. Indeed, ‘disco’ as a historical phenomenon was an idiosyncratic map of the symbiotic personal taste- and community-driven whims of the DJs who controlled the great ships of late-70s-mid 80s New York City, their audiences, and the artists in a powerful feedback loop. How it was reproduced among local communities in Detroit, Miami, Chicago, Los Angeles, and countless other regional outposts shaped the sound of popular music today. Yet this ecosystem of wildly influential clubs no longer truly exists—and even if it did, it’s certainly not shaping popular perceptions of records along idiosyncratic, personal lines of its curators. So what is the creative driver behind disco or techno today? Warring brand identities jostling for a presence within an agreed-upon Prestige format? Getting onto the Boiler Room or HÖR YouTube channel?

Of course, in techno, the stakes are different. Techno’s identity has become, of late, purely reactive, responding to disco’s uncontroversial dominance by embodying anything else. Techno became the home for every trend which surfaced as nominally interesting in the collective mood board—to revisit industrial music, the genre’s tropes and tics were welcomed, as long as they fell within techno’s formal remit; mid-90s trance, too, became a niche trend, alongside mid-tempo breakbeats. Yet these trends all seem to stake out their own fiefdoms within the genre’s broader conversation without really cohering into anything substantively new—temporary costumes, historical exercises which never fully disrupt the overarching expectations of techno’s hierarchy of clubs and festivals. Any subgenre is embraced halfway, not as a subversive effort to shift the formal characteristics of its genre, but as a different facet of ‘techno,’ a revival or re-appreciation that leaves the fundamentals unchanged.

Never are techno’s new stylizations able to gain momentum to overtake their parent genre, thereby challenging the primacy of disco. Meanwhile, endless iterations of novel creative ideas from Detroit 20+ years previous—*synth washes over kick drums imply a synthetic future shaded by tinge of wistful memory of the past*—retain a hold on the genre’s commercial center. Techno is the perpetual underdog, its trend and whim-driven intellectual’s dance music functioning like pre-World Series era Chicago Cubs management, filling the seats with fans but never taking it ‘all the way,’ leaving disco (the New York Yankees? IDK) in a tedious reign at the default top spot.

Of late, younger post-COVID clubgoers cranked up the tempo to 150bpm, turning audiences into bobbing hedonists. At least it was a new idea, and one which feels more fully in tune with the zeitgeist—albeit one which also further discourages ‘dancing’ in favor of the aggressive force of ketamine-addled will-to-obliteration. It’s almost punk-like in its negation of dance. In this iteration, techno becomes so anti-disco its impact on the body is at the level of fidgeting, heart-racing, quickening pulse rather than bodily engagement. If disco was retro re-articulation of a less-heteronormative “soul,” techno was the futurist re-articulation of “cool.” Yet both formats provide cover for aesthetic conformity and cliche. Meanwhile, the genre’s deified innovators and pioneers are granted a kind of brand tenure, and many have remained creatively relevant—yet their work is written about with a kind reverence which borders on mystification, generating cult-like enthusiasm but seldom impacting the ways in which the “genre” becomes an endless series of parodic imitations.

Some disco or techno of today isn’t mid, of course, including some names mentioned above—some songs I even love. One could argue, for example, that Dua Lipa’s embrace of disco as an aesthetic surface nonetheless retains purchase in the present through highly contemporary songwriting styles unlikely to be heard in 1978—a differentiating factor of contemporary relevance. In parallel, I’m a fan of the creative work of Boldy James, who, from a marketing perspective, is a quintessential Griselda-type artist. But this is a problem of art in an era of artistic overproduction. Here’s Richard Brody in 2019, warning of a parallel problem in the movie industry:

Despite the prominence of a few scattered prestigious titles, what dominates the streaming environment and overwhelms the popularity of any individual movie or show is the popularity of streaming itself—of a given service, whether it’s Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+, or another. What’s more, the popularity of streaming is similarly circular: the sheer quantity of what’s streaming also overwhelms the cinematic punditocracy with the sheer quantity of previewing, sifting, recapping, summarizing, comparing, and listing. The need to pay constant attention to the services rather than the works turns critics into connoisseurs of shit, comparing one mediocrity against another in order to be able to assemble a list of what’s barely recommendable with a straight face by contrast with what’s even worse. In the process, critical taste is inevitably shifted toward a new aesthetic (or anti-aesthetic) that leaves the best filmmakers of the time looking like backsliding conservatives clinging to ivory-tower traditions rather than what they are: audacious and forward-looking resisters to corporate production, not defenders but advancers of individual creation and conscience who overcome the redefinition of art as content—regardless of how their films may be marketed.

The problem of these formats is not simply that they funnel your ears with things you’ve heard before, but slightly worse, which can be ignored easily enough by sidestepping playlists luddite-style. But they also obscure the particularities of artists who are doing something consistently novel or creatively rewarding, simply because their best chance for audience exposure sits within the format, their creatively rewarding work shuffled somewhere around playlist position 8, jostling against 20 other acts for space in a marketing category which rewards deference to the spirit of the category rather than anything which might indicate an idiosyncratic style. This goes as easily for contemporary rappers like NoCap or Lil Poppa as niche artists in underground dance scenes. (Techno averts the playlist problem by being inherently underground—few people learn about new techno tracks from Spotify—yet this global network of clubs and raves retains an overarching adherence to a particular historic frame which defines its limitations in terms of the past—or a narrowly imagined future based on cliches of the past.)

Disco’s meaningfulness as a popular gesture waxes and wanes in different eras, but I’d argue there has never been a prior time in which the frequency of mentions so outpaced its creative relevance. Disco has, in the long run, won. It’s widely accepted as an affect of prestige cultural production, to the extent that it’s the byword inspiration for new Beyonce albums; any zoomer’s introduction to the genre supports a widely-accepted origin which mentions its origins in gay and black underground communities, and subsequent backlash in a homophobic, anti-black society, epitomized by the Disco Demolition rally at Comisky Park in Chicago—you know this story. So does everyone.

Bracket for a moment the ways in which it wasn’t the entire story—that George Clinton thought disco was “irritating,” one beat “sanitized to no end”; that revered critic Greg Tate coined the concept “DISCOINTELPRO” and characterized the genre as a corporate label-driven phenomenon, that the idea that there was a clear answer to disco’s social allegiances is overstated at best. Disco was embraced in part by upper-middle class whites, and many working class people saw disco’s aspirational aesthetics through its lens of upwardly-mobile sophistication.

Des McGrath: 'Yuppie scum'? In college, before dropping out, I took a course in the propaganda uses of language; one objective is to deny other people's humanity, or even right to exist.

Jimmy Steinway: In the men's lounge someone scrawled 'kill yuppie scum'.

Des McGrath: Do yuppies even exist? No one says, "I am a yuppie", it's always the other guy who's a yuppie. I think for a group to exist, somebody has to admit to be part of it.

Dan Powers: Of course yuppies exist. Most people would say you two are prime specimens.

—Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco

That’s not to say Clinton and Tate or these locally-oriented class warriors were right, or that they were right even in qualified ways, but that the connection of a music format to good politics is at-best reductive. It’s true in the grand scheme that anti-disco sentiment was downstream from larger societal bigotry, and that to stand with its audiences at that time politically meant substantial social cost. This isn’t to provide cover for those who didn’t take those risks, but to suggest that embracing disco now as if it were a transactional, consumerist choice that functions as a ‘vote’ for political allegiance fits well with modern liberalism—needless to say, not a popular position. Recently, disco reached a maximally uncontroversial embrace at its logical endpoint: country music’s return to disco in the form of hugely popular records like Miley Cyrus’ “Flowers” or Tyler Hubbard’s “Dancin’ in the Country.” Every part of America is well aware of disco’s ideological roots and doesn’t much care. In 2023, disco draws a line in the sand, across which only strawmen remain.

Likewise, techno’s futurist utopianism—not its only affect, but certainly a substantial one in its wider cultural mythos—sound a similarly liberal an off-note, in an era of now-widespread tech industry skepticism.

This lack of contextual awareness—where our knowledge of history hardens into guardrails which divert discourse away from our lived reality are exemplified by the responses to a stray Pitchfork tweet about Italo-Disco, in which hip young music nerds take a tweet to task for daring to suggest that Italo-Disco was ‘uncool.’

But Italo-disco was historically uncool—many of the people who championed it were embracing a tacky, camp aesthetic deliberately—and its very combative relationship to a temporal sense of ‘cool’ is what made it ultimately “cool.” But in this contemporary sanding down of history, contentious attitudes towards art designed to force you to take sides are elided in favor of a permanent “winner” and “loser” of history. An argument that Pitchfork is wrong to suggest that Italo Disco was ever uncool—when its very gauche aesthetics are what opened it up to become cool in the first place. “It was always cool,” as a statement is not always wrong, but often is, because it locates the art’s subcultural value in some static aspect of the songs themselves, rather than its contextual relationship with the wider world. Cool is not an objective fact but a contingent social one.

Today, one sides “with disco” with nothing ventured. It’s an empty gesture of solidarity when history has already been decided, for people for whom it’s always been a widely accepted and celebrated cultural force. Are they right? Sure, but what are the stakes when it’s so uncontroversial? There is a self-flattering sense of unearned valor towards past generations, as if being on the “right side of history” today doesn’t simply reflect a privilege of hindsight. Not only is the ink dry on italo disco, these tweets argue—the ink was always dry. Again, an individual’s relationship to the art and what it says about them supersedes reality.

Above: When you’re built different

Disco’s appeal, both initially and in subsequent reassessments and revivals, staked out specific aesthetic and ideological ground, sometimes to greater or lesser degrees; when there was an influx in disco edits in the late ‘00s, some producers, many of whom had graduated from collecting older soul records, cut out tonal choices that seemed ‘dated,’ like early ‘80s bass-slaps, or as often, those which seemed especially femme, aspects of the sound which resembled, say, musical theater—the very tackiness now on-trend in italo. This led, in that era, to a saturation of dull disco edits, many of which were inferior to the originals. It was actual-disco’s embrace of these “extreme” affects, those obviated or avoided by other genres, which made it an exciting and fertile (perhaps the wrong word choice) gesture in the first place.

Yet despite its historic powers broadening the cultural palette, it’s also worth mentioning how in some ways disco has tonal limitations insufficient to the present moment—of this, techno is not wrong. Disco is music which seduces; it is pro-social music, music for going out, music of aspiration, of sexual desire, and of communal and intimate expressions, music of pleasure. It’s this set of characteristics, when struck across a major American ideological fault line such as sexuality, where its claim to great political significance is made. Yet I would contend that today, disco is an odd tonal choice for a time in which younger generations have embraced a greater political stridency; it’s a time in which environmental devastation is at our doorstep, and the religious right is again resurgent. There’s been widely-noted decrease in sex, for a generation who have embraced anxiety as a dominant social affect. Here is a song by Cabaret Voltaire, from their 1987 album CODE, which I think better speaks to a reality that feels contemporary, politically relevant, and aesthetically fresh—as applicable to our current moment as when it was released:

Much as I’m using a 35-year-old song to illustrate contemporary relevancy, the song itself utilizes audio from a World War II-era United States Information & Education Division of the Army Services Forces film—incredibly, written by Dr. Seuss and directed by Frank Capra—to warn American soldiers about the dangers of fascist Germany. Its wartime mindset feels apropos at a time when trans identity is being criminalized and people’s lives are in perpetual danger, simply for how they present themselves in the world moment-to-moment. Surely, one might argue, “Don’t Argue” could fit within a disco setlist without much modulation—it already bears a surface resemblance to Prince, rooted in disco as he was.

This is true—yet through the disco lens, a song like “Don’t Argue” is marginal, an “exception-that-proves-the-norm.” I’d contend a more contemporary cultural vibe would shift closer to the aesthetic paranoia, the feeling of being surveilled, that I detect in “Don’t Argue.” This is not a call for disco to cease to exist, but to shift our attention to creative work which feels more relevant to present realities.

In some ways, this shift has already begun, particularly since the mass return to clubs following COVID, leading me to believe my increasing numbness to their aesthetic particularities is not a lonely one. It’s happening at all levels, where dance music emerges in popular new formulations—the rise of uptempo regional American dance music, particularly Jersey and Philly club, although sounds like Tre Oh Fie’s in Florida, and the modest rise of female-fronted Juke rap in Chicago, suggest there’s a wider renaissance of formerly-‘regional’ dance styles accelerated by tiktok; likewise, the globalization of Brazillian production styles, the resurgence of drum’n’bass and nu-garage among younger listeners, and of course the explosion of interest in phonk music which, despite its recherché vibes, was the fastest-growing genre of music over the past two years. Meanwhile, Amapiano’s arrival from South Africa, and the success of Ama-influenced pop stars like Nigeria’s Asake, are already impacted the global sound of popular dance. Incredibly, “cool” dance music, playing so abstractly with trendlets of history, lags behind the zeitgeist. The idea that dance music exists within popular nexus of disco and techno is already being eaten away as new trends poke their heads through, powered with new aesthetic allegiances—commonly, in a rejection of four-on-the-floor rhythmic template which defines both sounds at their core.

Surely, there is a third way. The past is always present, always relevant. That idea that old things no longer matter is a mystification not just of the past, but of the present, which is in constant dialogue with the past. Think about the function of musical gatekeeping in a pre-Napster music world. Here, the “generation gap” between the past and present was not measured as much in years as by dollars. In order to have access to the vast history of music, one needed to spend a lot of money. We were kept from perceiving the past, not because it “wasn’t present,” wasn’t relevant—individual communities did not lose touch with older styles, which kept them alive within a closed circle. But access to a larger collective past was blocked by the exorbitant cost of buying albums. Likewise, it was blocked by a popular discourse of history which championed specific formats—ie, Great Albums had a privileged position within a discourse which prioritized the audience for albums. The past was not difficult to access because it wasn’t relevant, but because it was obscured via profit motive.

Now of course, we have much wider (though still not complete) access to the past. Yet our attitude towards it is as if it is not a part of us, not related to how current realities. People’s relationship with disco and techno will of course remain inasmuch as they speak to what we experience. But I’d suggest that in embracing the past as an extension of our present, we acknowledge the ways the past relates to the present shift as quickly as we do. Being present means engaging with the past in ways which relate to our lives every day.

Good view and well said. We have strange a strange reality and responsibility with the fact that with the internet age all of this information/creativity doesn’t exactly die. But can be obscured and tampered with almost beyond its starting point. Weird to think about

🫡