What was "Turtle Power"

a subconscious desire to experience intensity of sensation

I mentioned in an earlier post that I felt sympathetic on behalf of gen z’s “wise naiveté” regarding “indie sleaze,” an ahistorical gestalt combining unrelated ‘00s social, cultural, and marketing phenomena. This interests me in part because electroclash, LCD SoundSystem, The Strokes—all this was itself a selective, curatorial ‘remembering’ of two decades previous; and the downtown art scene of 1980s New York, to which many of these bands paid homage, itself coursed with the creative textures of sound and style from decades prior.

I would not suggest that The Dare is the new The Sex Pistols, although people likely underestimate the cynicism that characterized the latter group early on. But an audience’s desire for something yet-to-be re-articulated is a constant. One hopes to impress upon the world their own experience of it—to be heard. Even those who would never be so gauche as to insist upon their own art nonetheless champion the obliterating power of Consumer Choice, to support what complements their perspective and push what doesn’t fit to the margins.

Artists in communion with with their peers, with an audience, with 13 people whose opinions they care about, nonetheless depend on certain foundational sensory associations which give their choices some form of meaning. The history of music more directly centers the perspective of dominant generations and the gist and limits of their storytelling, a shifting patchwork of inherited assumptions, reactions, often biased in the direction of our subconscious memories of our earliest sensuous experiences.

Our naive early experiences of music are treated as foundationally True, even though they retain as tenuous a connection to reality as “indie sleaze.” At the same time, as purely naive sensual experiences of a time they retain a ~more~ deeply True connection to the texture of the time, by ignoring the stories and sorting mechanisms that mediate our world as we mature. Likewise, as I sought to explore my own foundational experiences, and began to uncover what felt to me like hidden tributaries and caverns of the creative past. They were, and often are, trapped by the woefully insufficient popular narratives which often seem more concerned with justifying the present than explaining the past.

In my experience, most people assume the music of the 1980s has been pretty fairly picked over by reassessments, curators, DJs, and Dua Lipa albums. In revisiting my own barely-conscious sensory memories of the 1980s, however, I have found there remain several axes of ‘80s music prior or at the very faint edges of my own conscious experiences which resisted rediscovery. In some cases, they have been quite purposefully written off, particularly by those with “good taste.” My “in,” my gateway to a minimized history, was an obscure piece of popular culture known as the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

As a cultural phenomenon, this is ironic for two reasons. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were neither a particularly artful project in virtually any incarnation—the original comic strip by Eastman and Laird was an inspired marketing concept which functioned as derivative mix of their hero Jack Kirby and the then-ascendent Frank Miller, whose own obsession with ninjas in Daredevil and Ronin offered an obvious gritty blueprint; and the TV show, which introduced many of the more memorable and popular characteristics of the Ninja Turtles (ie pizza, “cowabunga”), still mainly existed to sell toys. (It is no coincidence that the best documented story of the Ninja Turtle phenomenon is a Netflix documentary about selling toys.)

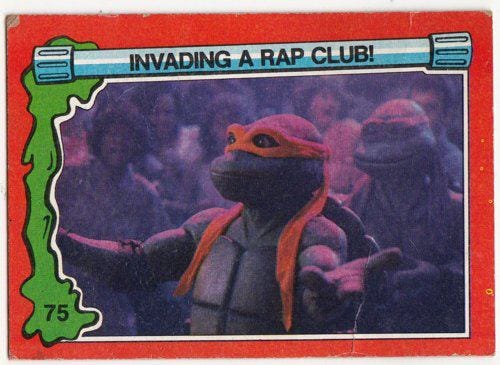

Secondly, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles never left. After saturating popular culture, the franchise has retained a perpetual presence year after year, in decidedly less intense articulations since the initial explosion of Turtle Mania (widely consider by Turtle historians to have lasted from 1987, with the creation of the television show, through 1992, when we graduated to more mature tastes, like Batman: The Animated Series.) Simply discussing TMNT risks giving “corny mid 2010s Buzzfeed nostalgia overload.” But this is also why it has explanatory power for me today. TMNT is an anchor to the past which is unlikely to fade to the background as so many kid-targeted pop culture phenomena of the time have. But why?

I (born: 1983) had such a strong attachment to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, as did many members of my generation, due mainly to a 5-episode cartoon pilot which premiered in 1987 and was passed around from family to family on F.H.M. (Family Home Entertainment)-branded VHS tapes for the next four years. It was solidified by two full-length feature films of varying quality (first one is pretty cool and features Jim Henson muppets) which arrived at the right time to capitalize on intense prepubescent fascination with the property. This was in the middle of a concomitant American fascination with Ninjas (which would reach its rational outer limit with 1993’s Surf Ninjas, one year after 3 Ninjas.); anxiety around environmental dangers such as the depletion of the ozone layer and radioactive mutagen; and—I suspect—stories of “nontraditional” families, often immigrants, eking out a living in multicultural modern America, torn between modernity and tradition.

Although the television series was released in 1987 and had an impact which lasted into the early 1990s, I contend that, canonically the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, then and forever, exist within mid 1980s New York City. This is also true of the 1990 and 1991 films. (I never saw the third—the Ninja Turtles by TMNT III were canonically Kiddie Bullshit). For one thing, they’re rooted in crime wave cinema of the early ‘80s, like a kid-friendly version of Death Wish 3. (By suggesting the crime wave is, at its source, the consequence of one specific malicious actor channeling kids into gang life, it’s probably less fucked up than Death Wish.) For another, they arrived in the wake of a phenomenal era of cultural significance for America’s largest city—the arrival of hip-hop and images of the burned-down Bronx were joined with conjoined with racist propaganda (cf Central Park 5, Bernard Goetz), but were also powerful renditions of a new American frontier, a massive, overwhelming and unconquered urban landscape, full of hidden crevices like underground sewers, heroic graffiti writers, and pre-google maps mystique.

The first issue of the TMNT comic (which I didn’t read until adulthood) specifies that the Turtles consider themselves police allies; in the initial cartoon pilot, they seem skeptical of authority, but are equally disdainful of teenagers listening to boomboxes. OK Karenatello! The ideological underpinnings of popular culture have shifted drastically in the intervening years. One great visual gag, depicted below, from the cartoon: a man reading a newspaper is covered in spray paint because he stands between a graffiti writer and a brick wall:

The graf writers themselves are dressed in Warriors-era New York fits, a blend of early hip-hop showbiz (leather jackets and downstream Rick James-type flashiness) and the mohawks, piercings and ephemera of downtown punks. As are the multi-ethnic street gang which harasses April O’Neill on behalf of The Shredder moments later. Culturally, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are early-mid ‘80s as shit, to the extent that a 2014 reboot movie spoke of a “crime wave in New York City” felt as out of touch with contemporary New York reality as a 2016 Donald Trump stump speech.

This reminds me of a passage from Roger Ebert’s one-star review of Death Wish 3, an important film in the history of ‘camp renditions of crime-ridden New York City.’

The neighborhood is ruled by a gang headed by Fraker (Gavan O'Herlihy), who wears a reverse Mohawk: He keeps his hair on the sides, but shaves down the middle, to make room for a gang symbol in war paint. O'Herlihy looks a little like Richard Widmark, and is quite satisfactory as a snarling, sadistic creep. He is also, of course, white. One of the hypocrisies practiced by the Death Wish movies is that they ignore racial tension in big cities. In their horrible new world, all of the gangs are integrated, so that the movies can't be called racist. I guess it's supposed to be heartwarming to see whites, blacks and Latinos working side by side to rape, pillage and murder.

Yet it’s this anachronistic quality which turns out to be the keystone connection to—most importantly, for our purposes—marginalized cultural textures of the mid-1980s. The compositions of one Dennis C. Brown (not to be confused with reggae artist Dennis Brown) on the first season of the television show and John Du Prez (on the TMNT I and II films) were—particularly in Du Prez’s case—dated pastiche by the time Turtle Mania hit its absolute peak in the early 90s. [More on Du Prez in a future post]. If these sounds seemed unusual at the time, its because they were, by the early 1990s. This was what New York had sounded like seven years earlier. Hip-hop had moved on—in large part, because samplers returned “organic” drums to the forefront—and by 1991 with the introduction of The Chronic, had introduced new geographical frontiers to a global audience. I don’t mean to imply that TMNT’s New York pastiche soundtrack was especially good (although I do enjoy it); more importantly, they were late, which for people of a certain age cohort, was right on time.

But why were these superficial, arguably diluted reproductions of significant cultural creative movements of the early-mid 1980s so effectively carried forward by a children’s cartoon show? The 5-episode TMNT pilot season remains, to my mind, the essence of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles as a popular culture phenomenon. It became the blueprint for the show’s long term success, tying the Ninja Turtles to lingo (“Cowabunga!”) and pizza, and the Turtle’s boy band-like distinctive “personalities.” This was through the efforts of a sci-fi writer and filmmaker-turned-television writer by the name of David Wise. Wise, the son of a staple member of New York’s downtown avant-garde theater scene, had been a prodigal childhood writer and filmmaker tutored by Harlan Ellison, Frank Herbert, and Ursula K Leguin while attending the Clarion Workshop. He went on to write Transformers and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, among other cartoons, about which he would spend decades answering questions thereafter.

One gets the feeling from his interviews that he felt a sense of frustration—despite his significant contributions to the show’s success, he was merely an employee of the television studio, and never partook in the greater wealth created by either the Turtles’ creators, or the Playmates toy company that indirectly employed him. But he did, in those first five episodes, create a compelling, world-building narrative that truly launched the Turtles as a worldwide phenomenon. As a kid, his story felt more canonically “true” to me than Eastman and Laird’s comic, or the movies which tried to split the difference. They have the strongest functional plot elements, new, well-defined characters, and character relationships—Krang and Shredder’s contretemps around the creation of Krang’s body. As Wise points out in an interview with “Cowabunga Corner,” LOL, the pilot season also contained a moment of real drama absent from the comics—when Splinter destroys the only tool which could return him to his human form, in order to save the Turtles from the Shredder, a choice that gave the series actual stakes.

The earliest episodes of the TMNT cartoon show, then, were the fulcrum for my understanding of who they were and where they were from, and as such, deeply associated with any strong feelings I might have about the franchise.

The theme song is written and partly performed (“get a grip!”), improbably, by television honcho Chuck Lorre, who went on to create Grace Under Fire, Cybill, Dharma and Greg, and Two and a Half Men. But the music which interests me, which I always associated with mid-’80s New York City, are Dennis C. Brown’s background productions, especially in the first episode in which our setting is established. Nowadays, looking backwards, I can hear the influences on these sounds—the sus4 chords common to nightly news shows of the 1980s, Miami Vice, the Miles Davis circa Tutu-type loping funk of the aforementioned graffiti scene, the drum machine-driven synthesizer funk from hip-hop of the mid-1980s. There was a narrow period, roughly 1982-1987, in which these sounds were a vision of the future, and just as quickly, came to seem primitive.

i was a bit too young to catch the ninja turtles so ideeply appreciate this as a way to better understand the art and history within the crass toy-selling nature of the IP. It’s interesting how the arcade game recently got the reboot—as a Netflix gaming app special 🫣.

Excellent