2023's Best CYBERFUNK Album

Raer contemporary cyberfunk release

CYBERFUNK is a metagenre pastiche conceived to capture the lost or diminished aesthetic vocabulary of the mid-1980s. The best way to understand the laws and byways of CYBERFUNK is to order Time to Make the World End, Vol III, a CD-only mix which explores the network of mainly obscure gestures which make up the sound. You can read more about it here, read a Q&A with ISIL CEO on the DJ Mix’s origins here, or explore ten cyberfunk hits you already know here.

But why read about it when you can experience it firsthand? Order the mix at ISIL.CLUB. Orders ship any day now; US only, for now. CD only, forever!

CYBERFUNK’s increasing visibility in contemporary music is largely accidental, a subconscious side effect of an Idea whose time has come rather than a conscientious artistic will-to-funk. As I’ve described in the past, it surfaces inadvertently and occasionally, seldom as the focal point but to increasing degrees over the past several years. When its signifiers do arrive as part of a conscious trend, they tend to be highly deferential to the spirit of history—essentially unimaginative yet precise cosplay—or they’re subsumed within the remit of techno, defanging genres like Industrial of the ‘rough edges’ which would enable them to sprout wings anew.

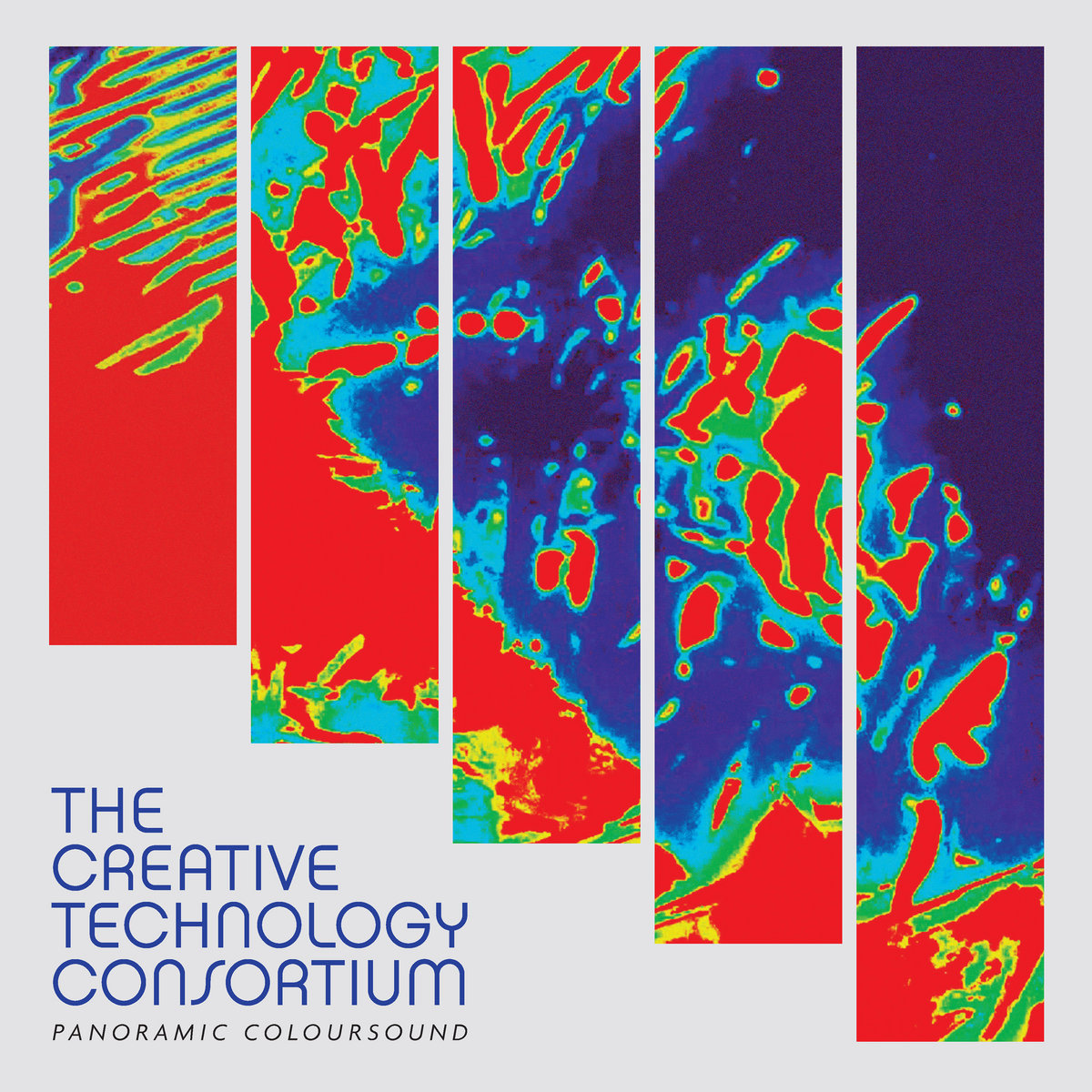

However I did love one slice of contemporary CYBERFUNK this year, one which, like this project itself, has roots in the homebound creative inspiration of the pandemic years of 2020-2022. The Creative Technology Consortium {CtC}, released a very enjoyable project last year entitled Panoramic Coloursound released through the Dark Entries label and available on Bandcamp and Spotify. It’s also being sold as a triple-LP set, though I don’t buy much contemporary vinyl these days honestly. (Still buy the old stuff.)

The venerable Dark Entries celebrates it’s [sic] 300th release with Panoramic Coloursound, a triple LP from the Creative Technology Consortium. Traxx, Andrew Bisenius, and Jason Letkiewicz forged the CtC during the depths of pandemic isolation. Drawing from film and television music of the 80’s/90’s and armed with a mighty array of vintage analog and digital synthesizers, they set out to explore heists, vices, and catastrophe. Panoramic Coloursound collapses sound and image into a neon blur throughout its 25 tracks.

While retro scores were the starting point for the CtC, the project does more than pay dutiful homage — these notes are warped and skewed, devolving into decaying digital soundscapes. EBM-inflected basslines pop up on tracks like “Catastrophe” and “A Retro Vice”, menacing numbers that recall Traxx and Letkiewicz’s legendary work as Mutant Beat Dance (a project also featuring Beau Wanzer). “Follow Our Kode” pairs heroic synths with funky bass, striking cosmic chords akin to the material that Traxx and Bisenius have released as An Anomaly. Krautrock-esque guitars slide along anthemic pads on “Beautifully Polluted Sunset”, which comes across like an alien Miami Vice closing theme. The CtC channel corroded VHS vibes while making music for the future. Panoramic Coloursound was mastered by Frédéric Alstadt. The sleeve was designed by Eloise Leigh, and features a photograph by Jason Letkiewicz. Also included is a postcard featuring liner notes, a gear list, and a photograph by Maria Tzeka.

I love that there’s also an insanely extensive list of gear utilized in the credits:

Mastered by Frédéric Alstadt

Design by Eloise Leigh

Cover photos by Jason Letkiewicz

Band photo by Maria Tzeka

CtC Electronic Gear List:

Prophet VS

Korg M3r

Sequential T.O.M.

Lexicon PCM 70

Eventide H3000

Strymon DIG

Akai AX73

Access Virus B

Elektron Digitone

Elektron Digitakt

Roland JX3-P

Roland D-05

Sequential Circuits Drumtraks

Yamaha SY77

Yamaha RX 21

Korg Wavestation A/D

Roland 626

Korg Microkorg

Yamaha DX100

Sequential Circuits Pro-1

Roland SH-101

I think what makes it overlap so well with the goals and ideals of the Time To Make the World End mix series, Industrial Streaming Information Logistics ideology, and general CYBERFUNK gestalt, is the trio are more interested in recombination of vibe than isolation or recreation. At its best, the project captures certain alchemical blends of melody, texture, and timbre to float around like ghosts of 1980s memories: Miami Vice, movie soundtracks, industrial funk, the poetics of the era’s multimedia. It does tend to fixate on a mode and ride it out, creating slices of mood-music one could envision describing as ‘trip-hop’ or ‘instrumental hip-hop’ with slightly altered source material to drawn on—that is to say, it seldom approaches pop, or contends with especially elaborate structural choices which might allow it to expand beyond its reliably satisfying rolodex of memory-tapping affects. But I listened to it a bunch, and found it was easy to get lost in its particularly on-trend set of tonal connections.

It also helps that TRAXX is one of the great DJs of our time.

First off, I’m biased, because TRAXX went to the same elementary school as me, several years before I did. Second, I’ve seen him in Chicago a few times, blowing the roof off Danny’s Tavern and upselling me on buying two cassettes even though I didn’t own a cassette player at the time. I also saw him in Detroit during Movement, probably the loudest DJ set I’ve ever heard. Each time I’ve seen him, he had a forceful confidence in a sound I hadn’t heard from anyone else. TRAXX operates independently of trends, a true -setter not -follower, just by becoming an increasingly embellished version of himself. It feels like the pendulum has swung back to where the kind of records he’s liable to play—industrial/EBM, rock, house and techno that leans into texture and timbre, a formally unpredictable future-primitive vibe reminiscent of a construction yard.

The TRAXX aesthetic—distinct though overlapping with CYBERFUNK—is one labeled Jakbeat, and it cohered in the mid-aughts. In 2007, Traxx founded his own label Nation, which allowed him to further elaborate on this sound. In contrast with CYBERFUNK, Jakbeat is oriented around a specific essence that feels indebted in certain ways to his early exposure to WBMX radio’s Hot Mix 5, Frankie Knuckles’ Warehouse, Medusa’s industrial nightclub, Ron Hardy’s druggy, psychedelic Music Box; the impact of Acid House, which makes up a substantial part of the genre’s DNA; and a specific meta-aesthetic ‘feel,’ the urge to jack your body as the songs say. The Nation website used to describe the ethos thusly1:

In detail what defines jakbeat tracks has a lot to do with the jacking feeling and little to do with labels, aesthetics, or any list of synthesizers.

The Jack sound exists in an endless assortment of musics.

For a while it was generally known that you do not need a Roland TB303 to make ‘acid’. But as other fashions took control of our house that fundamental understanding was lost…and the aesthetic took over.

A contrived image was left with the masses.

Jakbeat as it has come to be known is a not just a hash back to a golden age of house, it’s not just a mess of drum beats and synths and it’s not just something that is created at random.

“Jakbeat” is a state of mind and different level of musical consciousness.

This sound was influenced from the early inception of dance music.

As a collective we want to produce an impressive slew of no-holds-barred full on electronic/synth rhythm tracks resisting the current trend for an over-calculated digital sound which has retained the musicality in keeping it very real.

I was particularly drawn to his rejection of traditionalism and the hardening of arteries that is the commercialized contrivance of genre. In a 2008 interview with Traxx2, he described his influences in Chicago as mainly being about parties, not formal aesthetic choices, and goes into depth on those influences. He also articulates the explicit styles that make up his sound:

It's a truly separate genre in its own right... the reason is because jakbeat is influenced from not just by techno and house, it derives from elektronic body music, freestyle, disco not disco, punk-goth, synth pop music, minimal wave (meaning rare tapes) and italo... Our sound cannot be created at random... it's a state of mind and different level of musical consciousness: hypnotic patterns and melodies to push the envelope of comprehensible dance music.

The main problem in music is the will of everybody and especially journalists and professionals to categorize points and put things in boxes.

Traxx may as well have been anticipating the reaction to his 2009 debut album Faith, which received middling reviews from Steve Mizek (a journalist behind the old dance-oriented blog Little White Earbuds) in the Chicago Reader and William Rauscher in Resident Advisor. Both—especially Rauscher—keep hammering home this idea that Traxx’s album was the product of a retro-obsessed traditionalist: “Faith fits squarely into this scene, being a full-on dive into first-wave Chicago house that expresses its love for tradition…So if you're not in the mood for some retro house action you might want to keep walking. Faith is so chock full of classic-house signifiers, it's basically a de facto style guide….” He echoes arguments Phillip Sherburne was making around the time that there was an increased historicism and decrease in innovation, increase in musicianship, decrease in rule-breaking.

The characterization of Traxx’s music as particularly reactionary or traditionalist feels somewhat absurd in today’s context—what he was articulating was not simplistic reactionary cliches of “house is a feeling” as Rauscher asserted, but that a unifying personal vision, idiosyncratic as a snowflake, is beyond his own articulation: "The point is that when you try and describe it, sometimes that feeling is lost. It's like when you're looking at a painting and try and describe it...you'd rather just be absorbed in it, melt into it…”

I’m reminded of Harry Allen’s recent (great) piece for OkayPlayer on the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, when describing how Kool Herc’s radical vision reshaped the entire field of popular music:

In other words, Herc came of age in a rich, fairly mature, and highly influential Black disco subculture, and drew from a buffet of possible approaches. Gifted and dogged researchers are still teasing out the neural pathways of what he saw, but what we can best say is it was profoundly nonlinear. Tentatively, what may ultimately become clear is Herc observed everything he performed in some other setting — including funk breaks and repetition — but not necessarily in one place. Most of all, none of what he saw was aimed at a teenage audience eager to be beguiled, and for whom every aural delight was new.

Not that I’m suggesting Jakbeat is as significant a reimagining of its time as Herc’s vision was for his—although how much of that is mere accident of timing and history is certainly debatable—but it’s a near-identical methodology. A profoundly nonlinear approach to genre in which the artist’s vision finds unconventional and underutilized links between seemingly unreleated historical phenomena. History is important for understanding the stories we tell about how music evolved and developed; as important is artistic revisionism, because it gets at greater aesthetic truths about how music functions along the lines of communal memory.

Everything Traxx has produced does not fit within the CYBERFUNK purview—minimal synth, acid house, disco-not-disco—all of these styles have been relatively ‘on-trend’ since Traxx was dropping records with DJ Hell in the early ‘00s, and bear little relevance to true CYBERFUNK aficianados. But his vision has remained remarkably consistent. An amazing piece by former Chicago Reader social columnist Liz Armstrong inadvertently captures the beginning of the arc of industrial’s reappraisal—once the red-headed stepchild of Cool Music, as evidenced by the following: “I’ve never seen Hell spin, but Traxx patches together a schizophrenic jumble of house, punk, new wave, bad industrial goth, and whatever else he feels like.”

I love this quote because people so seldom will admit to this kind of thing after the style has been reappropriated by cool-chasing DJs, creatives et al. “industrial goth” hasn’t been considered “bad” for several years now, and it was pretty uncool (though popular, if marginal) until pretty recently. But it also points to the truth about Traxx’s aesthetic universe: it’s been strongly personal and consistent over the course of 22 years, at the very least. And what was suddenly out of trend appears much more legible as the full force of his vision appears more and more “on trend.”

To close out, here’s another parallel with CYBERFUNK, and something that may have appeared “traditional” at one point, but feels positively rewarding now: Traxx’s use of hardware over software. The idea of dragging waveforms around with a mouse—of sitting at a computer in any way—feels absolutely repulsive to me at this stage of creation. Not because I have some kind of traditionalist devotion to hardware, but because sitting at a computer is tedious. Here’s Traxx’s perspective, as quoted in XLR8R:

So everything before the computer is analog?

Yeah. For example, I use one of the first sequencers from the ’80s. It’s called an Alesis MMT-8. I do have some VSTs in my studio, like the [Korg] MS20. But I’ll tell you right now that basically the entire album, Faith, was done with analog gear: Roland synthesizers like the SH-101, a Juno 106, and the TR-707 and 505 drum machines. Or I’ve got a Korg Poly 800 and this German acid synth, the [Acidlab] BassLine…I’d rather allow for more of the human part, the old machinery that gave out that certain signal; that certain frequency…True, everything around it sounds so raw.?

And that’s a choice that you can make, even if it’s a choice that not everyone seems to realize they have. For me, I just feel better using these machines because I have to work. I have to actually do something. Lift my fingers up and move around and get the exercise. And you know what? A lot of people making the music right now could stand to do the same. Do some work! Step up your game. I don’t want to hear that shit anymore—half these people aren’t doing anything. They’re just talking and bull-jiving. What happened to being diverse? What happened to taking real risks? Because to me, these people—and they know who they are—they’re saying, “I want to make my money by being safe.” If you’re making the music, let me see you actually do it!Is there a connection between “doing work,” like physically moving, and taking risks as a producer?

Absolutely.In that respect, you’re probably one of the most physically active DJs out there?

Yes, although let me make this point, if I can: I am not a DJ, I’m a disk jock. There’s a big difference there. I am not your request. What a disc jock is supposed to be is a medicine man, a shaman. And I don’t give people what they want; I give them what they need.

https://www.dmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2012/01/whats-jakbeat-style-pioneer-traxx-aka-melvin-oliphant-iii-is-in-denton-to-show-you/

https://www.smartshanghai.com/articles/nightlife/interview-brtraxx

More from that last XLR8R interview:

Do people need to hear some of the past again?

Well, it’s like… my beat patterns always come from myself, but I do listen to the old tracks and I do try to take those old patterns into a different place. But just so you understand this: It is not copycatting to take those ideas and go somewhere else with them. It comes from this whole jack thing, spelled j-a-c-k. It’s an idea that’s made from the house music concept, but not in a way to rehash what we already know. And the thing is it’s not like I’ve been producing for like 20 years. I started in 2000, and I’ll be completely honest with you—I’m not a pro. But I do know enough to know what I don’t want things to sound like.

Overproduced?

Yes, and you get a thousand claps for that. I’m not sure how to say this, but… I’m taking from inside of the machine, and working from the inside backwards. I don’t know if you know what I mean. But I’m not going by the laws of physical gravity. I’m going by the alternative.