Welcome to ddrake.substack.com, a substack written by former music journalist/current industry A&R David Drake. This substack is one dimension of an art project I’ve been working on, one which manifests primarily as a series of DJ mixes courtesy Industrial Streaming Information Logistics (isil.club) exploring a sound I’ve labelled cyberfunk. In contrast with the predominant strains of retro dance culture—particularly disco and techno, which I find boring—cyberfunk has largely been marginalized as “dated” since at least the early 1990s. This substack is an effort to explore the real histories of a fictive genre, and have some fun. Listen to one such cyberfunk mix here.

When I was approaching my 30s, “going out” became very boring. How many times, I remember thinking, can I hear DJs play the same shit—how many nights can “a DJ save my life”? No way is it already time for the percolator! Sometimes the people working the night shift get caught in a rut; and, as with most things, there are more mediocre DJs than good ones. For everyone, those earliest explorations of nightlife leave a lot to live up to—you can only experience the peak-time venue, drug experience, rave, or a really fun crowd, so many times before the seams show—the bathroom smell, the sticky floors, the attendees who are rude or gross or bring down the vibe. And the DJs, who so easily slip into greatest-hits mode, as was happening at the turn of the 2010s. Sure, I’d grown jaded. But I’d contend in the wider world when EDM was ascendent, nightlife DJing, at least in Chicago, was going through a creative slump.

Then one night, my friend Grady took me to the now-defunct Neo nightclub in Chicago. It was founded in 1979, beginning as a new wave club and veering into industrial, punk, and house, with a general goth sensibility, as the decades wore on. It was open until 5am on Saturday, and the dance floor was packed until close. You entered through a back alley. Smoke machines pumped through the room. It looked, as my friend Josh would suggest, like the bad guy’s hideout in a mid-’80s action movie. (In fact, its last remodel, in 1988, was inspired by the appearance of Lower Wacker Drive—now perhaps most known as the setting for a memorable chase scene in The Dark Knight.)

I had heard Neo, the protagonist of The Matrix, was named for the venue—after all, the Chicago-based Wachowski sisters were noted fans of industrial music, claiming in interviews parts of The Matrix were written to “Just One Fix.” But in a great Leor Galil piece on the history of Neo, Lilly Wachowski disabuses readers of any direct or deliberate connection—giving some space for the fuzziness of artistic inspiration that I elect to believe means some relation is squarely the realm of ‘highly possible.’

In her early 20s she sought out venues and clubs with a more aggressive punk style, including Exit and Dreamerz in Wicker Park. She liked the Jesus Lizard, Public Enemy, and Rage Against the Machine, and her impression of Neo didn’t square with those interests. “I perceived that as being, like, a more affluent crowd, even though that was my perception as somebody that was more into angrier music,” she says. “All of the music that I was into was because I was an angry individual, because I was in this body that I wasn’t happy in.”

…

The Matrix, the second film written and directed by Lana and Lilly Wachowski, came out in March 1999. (Lilly is not involved in the new The Matrix Resurrections.) Lilly knows that many people imagine The Matrix to have some sort of connection to the nightclub Neo, and she’s willing to indulge them even though she never went there herself. “Art doesn’t form in a vacuum,” she says. “We’re all influenced by everything that comes before us. I can’t sit here and say for sure that the club Neo—‘Oh, definitely not!’ It’s not like we said, ‘Hey, we love that club, let’s name that character this.’ It was the name of a club, and we were writing a lot about underground scenes.”

Wachowski encourages people to interpret her work how they will, with one big exception. “I want to put my foot down in terms of the alt-right and what they’ve done to the idea of red-pilling,” she says. “That gross misinterpretation is something that really goes against the essence of the movie. So I’m happy to put my foot down every once in a while.”

She’s far more generous toward the people who’ve seen their favorite nightclub reflected in The Matrix. “I think human connectivity is where all of our movies have ended up going towards,” she says. “All of our movies are, at their base, about love and human connection. The fact that people who went to this club are saying, ‘They named it because of this,’ I think that’s cool. I like that.”

At the time I discovered it, Neo was lower-case c cool, but not capital-c Cool.1 The Cool dancefloors of the bloghouse era were rarely as small-c-cool as they wanted to be, but by the end of the ‘00s, they’d totally lost the sauce. What was cool about Neo was that it had no pretense of being Cool. Folks in pleather and goggles and questionable dreadlocks and cyberpunk gear embraced a long-running subculture which was out of step with contemporary trends. (Much of this stuff would scan as highly on trend today.) And most importantly, people would actually dance, get lost in the music, the baseline expectation of a good club, and would do it with an unselfconsciousness that felt unusually welcoming of idiosyncrasy.

Most importantly for me, the scene offered a “way out” from what had become a really staid moment in Chicago nightlife. But it was also a kind of creative reset. I knew one of every 20 songs—it was immersive in a way that felt liberating. I’d never been really drawn in socially by industrial music, Nine Inch Nails, ‘goth’ as a social category, etc. Aside from a friend who really liked Beaucoup Fish and some Aphex Twin, the wave of IT guy music hadn’t resonated for me to that point. By the early 2010s, it felt like a place I could go and feel like I was 21 years old again—experiencing clubs for the first time, not being able to predict what the DJ would play, lost in a world that was largely outside my experience, but nonetheless dancefloor-oriented. Their Thursday new wave nights were among their most popular—I have residual memories of dancing to New Order, which at that time would have just reminded me of college. But I found myself being pulled more by the darker, more hypnotizing funk of the hardcore EBM and industrial they played on Saturdays, which few other venues in the city seemed to touch by the late 2000s. The late night club became a regular Saturday night destination until I left for New York in 2012 (it closed permanently in 2015).

It took a few years for me to really leave that novice stage—I indulged in my own naiveté. But from that point, Industrial music became a growing interest of mine. In part, I was fascinated by its cultural connection to my Chicago hometown. It was curious that the city seemed to house such a uniquely underground form of dance music—as a longtime fan of House, it made sense to me Chicago’s underground rock scene might have a greater sensitivity to the dance floor, even though most of what had been canonized—your Wilco’s, your Urge Overkill’s—didn’t. The industrial sound was, though not totally ignored, critically marginal.

As the 2010s progressed, I also found that industrial spoke in interesting ways to a kind of ideological evolution within broader discourse, with the rise of social media, of an increasingly explicit politicization, as a distrust of popular culture, of media, of technology, of the control machines of modern society seemed to explode in reaction to the glitzy celebrity-adjacent naiveté of the Obama era. All of a sudden, by the Trump era, it had become something that felt more real to me than the more allegedly relevant affects of the period.

Since that time, I’ve gathered that I’m not alone in sensing a broad shift away from certain explanatory frameworks—the skepticism of poptimism (however misunderstood) and pop culture, of the ways in which our siloed media timelines have been manipulated and are vulnerable to bad actors—and towards the paranoid and conspiratorial. The well-intentioned efforts at producing Empathy for the right-wing manifestations of these skeptical attitudes, while ultimately misguided, are further evidence of a shift away from the old arguments of the Obama era and towards new terms of engagement.

I would argue, controversially, Industrial music, is less interesting as a genre format than as the creative texture of a very specific historic period, one with contradictory, yet highly specific and frequently articulated, ideological implications. “Industrial music” has certain cliches handed down over time, but their effectiveness is neutered in trying to recapture the spirit without adopting to a contemporary reality; I think in some ways, much of it may even feel kitschy. Yet some aspects of this history feel deeply relevant today. Why?

A good book to explore the history of industrial music is S. Alexander Reed’s Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music which I found does a reliable job of explicating the underpinnings. I’m going to briefly summarize the foundational influences on the form here, though I’d really recommend exploring his book directly yourself. I imagine I’ll end up revisiting it on this substack a few more times before this project has concluded.

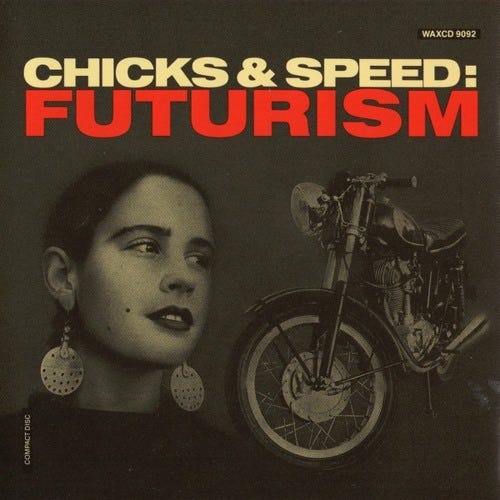

Industrial was inspired in part by an early 20ths century movement known as Futurism, articulated in a manifesto (loving this already—manifestos are definitely Back) by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. The Futurists were mainly Italian artists who strove to embrace the vanguard, the cutting edge, to the extent that this meant running headlong into audience confrontation. Modernity, speed, an embrace of the future, the aesthetics of mechanization (a direct consequence of the recent industrial revolution), and violence. Here’s a characteristic Marinetti quote: “Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack.” This manifested in books like JG Ballard’s Crash, which of course was adopted into a Cronenberg classic. But Industrial acts would also cite Marinetti explicitly—one of the most important things to know about industrial is that its a form in which Futurism and its related philosophies were always a part of its surface.

Another major influence on the formation of industrial music was William S. Burroughs. I’ll admit I’ve never been a huge Burroughs reader, though I did find myself deeply confused in an interesting way by Naked Lunch as a teenager. I’ll let S. Alexander Reed, author of Assimilate, explain the significance of Burroughs’ contributions:

If industrial music is one part optimistic techno-fetishism, its other indubitable twentieth-century precondition is every bit as literary as Futurism, if more cynical.

William S. Burroughs, a techno-paranoid American author often grouped with the beat movement, contributed two ideas to industrial music specifically. First was the alignment of authority figures and controlling agencies into one metaphorical identity of the machine, and the second was an artistic means of exposing, questioning, and subverting humankind’s mechanized enslavement to this machine.

Burrough’s fiction is generally interpreted less as storytelling than as sociology, tactics, and philosophy. Burrough’s outspoken distrust of tradition, authority, and order has roots and manifestations in his life prior to and beyond his writing, and indeed much of his oeuvre is essentially autobiographical…

…

A Harvard dropout, Burroughs was a social misfit, both effeminate and violent. His evasion of military service during World War II, his homosexuality, his drug addiction in the 1940s and 1950s, and his expatriation to Mexico all bespoke a seedy unfitness to dwell in the day’s whitewashed America. His most unsavory moment came in 1951, when he killed his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, in what was allegedly a bizarre accident. Vollmer, a unique exception to his sexual preference, was playing “William Tell” with Burroughs at a party in Mexico City; firing his gun while drunk, Burroughs missed the water glass she’d balanced atop her head and shot her in the skull. As he was awaiting trial, his brother bailed him out and he left the country. He was found guilty in absentia but never served time. (For what very little it’s worth now, Burroughs would express constant repentance and sadness over the incident for the rest of his life.)

Burroughs writing career hadn’t started to this point, but it’s easy to see how someone with his background might have a very unusual set experiences on which to draw. He attended the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico which the U.S. government would commandeer for development of the A-bomb; he became a fugitive in the early ‘50s, when the media was awash in very sincere propaganda regarding Soviet brainwashing; his drug addiction, sexuality, and general lifestyle were not merely frowned upon, but seen essentially as a mental condition. Paranoia, understandably, became a dominant tone in his work:

In his post-Junkie work, he uses the term control machines to refer to technology, religion, government, and language. The control machine can be seen as a peculiar version of Debord’s spectacle, Adorno’s notion of “the culture industry.” These models all vary in their specifics, but they identify an overarching set of invisible connections between hegemonically ubiquitous cultural entities.

The confounding feeling I got reading Burroughs as a teenager was of course intentional; to Burroughs, it was a method of combatting control machines, that by resisting their formal structures one can break out of the addictive model of those institutional norms. (A former junkie, Burroughs’ drew a clear parallel between drugs and the allure of the system.)

Anyone who has tried to DJ using even the dancefloor-oriented industrial music of the mid-1980s will notice some substantial difficulties, at times, keeping the tracks aligned—loops don’t necessarily loop in four- or eight-bar segments; the “one” at the beginning of the song may end up the “three” halfway through, then “the four” by the end. Here we have a technique that I find especially exciting in industrial, as exciting for its potential in current music as in its historical form. Industrial music’s embrace of the unexpected, of suddenly violent noises (from Futurism) and unpredictable and unconventionally-structured forms (from Burroughs), was a paranoid reaction to oppressive control systems—a strategy of breaking out of conventional tactics.

The “cut-up,” a Burroughs-embraced technique of juxtaposing pieces of media to cultivate new and deliberate meanings, another technique which would litter the work of industrial acts in the 1980s, with movie dialogue and political speeches chopped up and rearranged over songs to broadcast an intentional agenda. This was all done in the spirit of anti-authoritarian resistance, a way of embracing technology and rejecting its formal limits simultaneously.

Many of these techniques will strike people, correctly, as being pretty similar to what was happening in hip-hop at the time, in its own way, and without sharing any of the same philosophical bases. Exactly, you’re getting it—this is Cyberfunk.

I’m leaving this intentionally vague but I think you could interpret small-c cool as “lacking in obvious glamor but very fun in ways easy to intuit yet rarely explained.” Any glamor is retroactive. I’m not against capital-C Cool, but Cool places that are not also cool do tend to suck. Capital-C Cool depends a lot on fun to overcome its pretensions.