Welcome to ddrake.substack.com, a substack written by former music journalist/current industry A&R David Drake. This substack is one dimension of an art project I’ve been working on, one which manifests primarily as a series of DJ mixes courtesy Industrial Streaming Information Logistics (isil.club) exploring a sound I’ve labelled cyberfunk. In contrast with the predominant strains of retro dance culture—particularly disco and techno, which I find boring—cyberfunk has largely been marginalized as “dated” since at least the early 1990s. This substack is an effort to explore the real histories of a fictive genre, and have some fun. Listen to one such cyberfunk mix here.

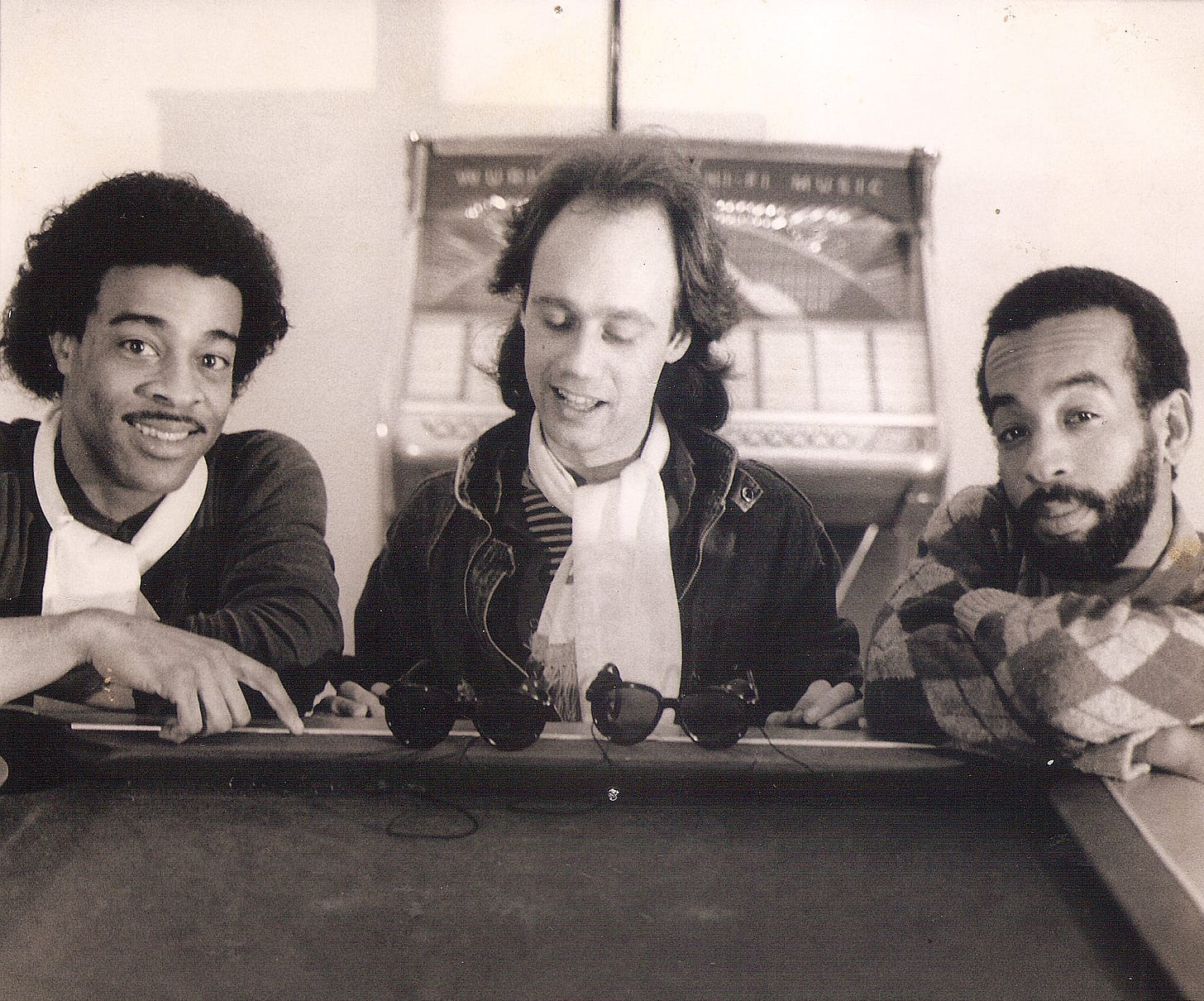

The best american band of the 1980s is the trio of Skip McDonald, Keith LeBlanc, and Doug Wimbish. The spinal cord of the decade’s best music, a profoundly modern phenomenon in their own right, the group lived so deeply in the texture of culture they became illegible to a publicity-ordered world. Who innovated the air you breathe? The assumptions made about who matters, about what’s good and what’s bad and what’s important and what’s insignificant, what’s influential, what’s fly-by-night, a perpetually ineffectual argument between bubbles of subjective consumer preference, of familiarity, all float soundlessly to the surface in a pool built by the best cyberfunk band of all time, a machine that structures the sounds of our present and future in 2023: Tackhead.

The case is easy enough to make. As the house band for Sugar Hill Records, they (along with Sylvia Robinson) were directly responsible for the central plank of earliest recorded hip-hop, the first to adopt the innovations of the genre’s DJ creators into saleable compositions of recorded sound; as the house band for Tommy Boy Records directly after, they solidified that role and extended it. As a solo group with UK engineer Adrian Sherwood, they spearheaded the marriage of technology to studio musician funk, pioneering sounds replicated by acts across genre thereafter. As collaborators with Sherwood and legendary Jamaican drummer “Style” Scott, they created unique dub records as Dub Syndicate. As collaborators with Mark Stewart, Ministry, and eventually Nine Inch Nails, they cultivated what would become the most popular and widely understood rhythmic template of industrial music. And as hired hands with Trevor Horn, they came to define the sound of pop going into the ‘90s, underlying Seal’s debut, for Tina Turner, and Annie Lennox; Wimbish joined Living Colour and played with the Rolling Stones. The common denominator of some of the best music of the 1980s, the most overlooked and under-heralded cyberfunk of the decade, their music sounds further ahead of its time now than it did even in its infancy, when every trick they pulled was emulated by everyone from Paul Hardcastle (inspired to make “19” after hearing LeBlanc’s “No Sell Out”) to KMFDM to Prince (“Every time we put out a record, Prince would come out with a record that had the exact same beat I put on a record. This happened quite a few times.” -Keith).

Tackhead’s best work as a solo recording act mostly isn’t readily available in its original versions on DSPs—a series of 12”s with UK recording innovator Adrian Sherwood cut across the mid-1980s, songs like “Mind at the End of the Tether”/ “King of the Beat” and “What’s My Mission Now?”/ “Now What?” are the piston-pumping exposed-engine mechanical heart of the decade’s technological id. (Newer/different versions of these 12”s are available on 1988’s Tackhead Tape Time, avail on DSPs, but to my ears the mix gives these records a tinnier sound than they have from the 12” singles, and slightly different arrangements.) They were every A&R’s favorite band—innovating at a regular clip, trying out each new piece of gear as it was released, and inevitably inspiring a wide cross-section of acts struggling to keep up with the sudden tectonic technological sonic shifts within popular music.

Of course “innovation” is a frustratingly backhanded compliment; plenty of music fans will treat ‘innovative’ groups less as artists than laborers who can be shaken upside-down for the coins rattling around in their pockets, subsequently scooped up by their own fav acts. It also becomes tediously debated; when LeBlanc claims they were the first to embrace sampling with the AMS sampler, some pedant can surely uncover examples of “samples” being used prior—an empty competition in which no one ends the winner. Yet what makes Tackhead’s run of early singles (including those under pseudonyms like Fats Comet) exciting is how they more fully embody the cyberfunk ethos than the acts which used the band to overlay their own vision and personality on top. Tackhead were sonic scientists, producing a genre-agnostic template for popular music that felt at once shockingly experimental and infinitely adaptable to any of the acts they could work with across scenes, sounds, and styles. They were the DNA.

For drummer Keith LeBlanc, this meant in part a constant reinvention of the rhythmic template; if disco’s strength came from a monorhythmic adherence to a structural lock-in that allowed for endless variety within the limitation, LeBlanc’s constantly shifting rhythms offered a ‘way out’—to innovate forms, new foundational structures that shaped musical futures. As he would put it in interviews, everyone else used drum machines to emulated drummers; as a drummer, he used drum machines to figure out what drummers couldn’t do. “DMX quantized up to 96th notes. No drum machines even do that now. So I was able to take the toms and timestep ‘em in and make these drills, like these jackhammer drills in rhythm. And then I would open the box and tune ‘em while we were recording. People thought I was crazy, but they loved the sound. That was a pretty copied sound.”

In this era, as tapes shifted to CDs, a group like Tackhead was working at a pace that matched the post-Napster mixtape boom, where streaming was more or less invented by innovators whose prolificacy was matched by their pace of relentless creativity—the formalist signal in the noise. In the 1980s, this kind of formally creative genius was forced into the old rock-centric album auteur formatting. What Tackhead did outpaced this, even if as solo artists their work remained marginal and never attained a cross-generational audience. Their perpetual reinvention was a tool appropriated by the industry, but not in and of itself a saleable commodity—ironic for a group who’d translated hip-hop’s unsellable essence to a recorded medium themselves.

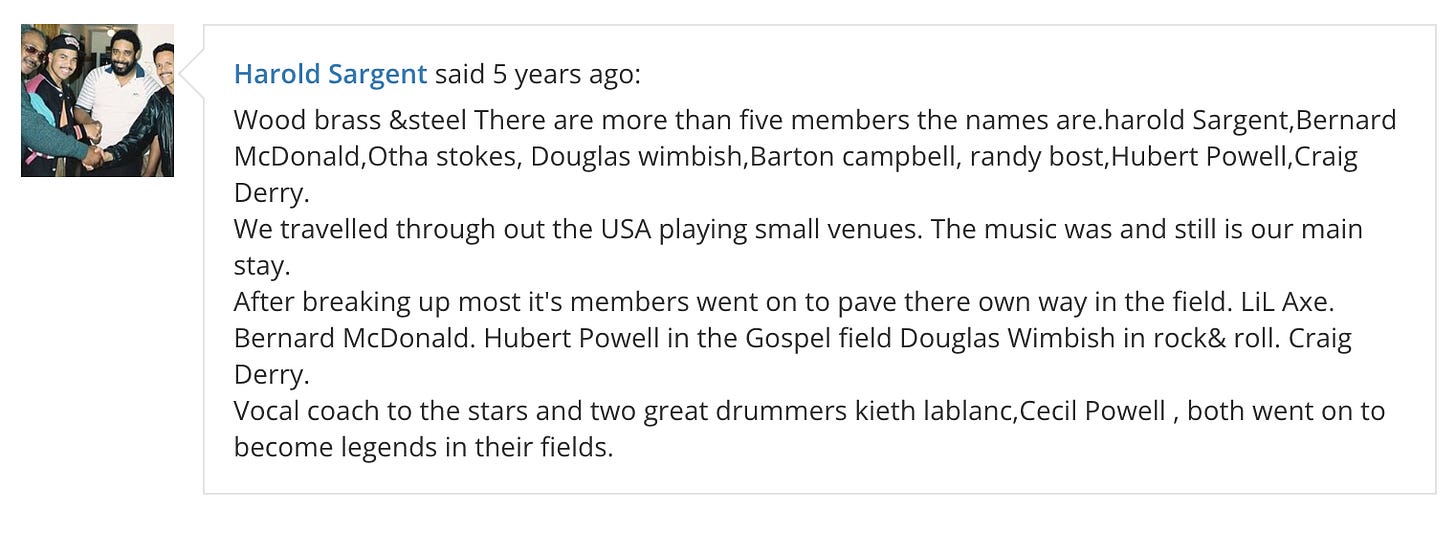

Tackhead was created inadvertently, albeit with some intention by legendary songwriter, producer, arranger, and (not least of all) musician Harold Sargent, who passed away in 2020. He was the drummer behind “It’s a New Day” by Skull Snaps, for which he never received credit, one of the most sampled breaks in popular music history (Pharcyde’s “Passin Me By,” Gang Starr’s “Take it Personal,” “Butterfly” by Crazy Town, “Clubbed to Death” by Rob Dougan). He was a drummer for the Escorts; he produced Sparkle’s classic “Disco Madness.” In the late ‘70s, Sargent was in the group Wood Brass & Steel with bassist Wimbish and guitarist McDonald, and they had a reputation as Connecticut’s best soul band, notching two modest hits with “Always There,” a Ronnie Laws cover, and “Funkanova,” which would surface in Kenny Dope and DJ Sneak house records down the line.

When Sargent was leaving the band, he introduced a rookie drummer named Keith LeBlanc to McDonald, and suggested him as a replacement. LeBlanc joined Wood, Brass, and Steel at an epochal time in music history. Everyone has a link to WhoSampled and Discogs, you can make these connections, too. Sargent did himself, posting a comment on WhoSampled two years before he passed:

The band that plays on “Rappers’ Delight” is a Philadelphia group called Positive Force. Sylvia Robinson of Sugar Hill Records had attempted to hire Wood, Brass and Steel, but the group had brushed her off; Positive Force (who had a UK hit with “We Got the Funk” on Sugar Hill) were brought in instead. The future members of Tackhead recognized their mistake the moment they heard “Rapper’s Delight.” Almost every major release on Sugar Hill from that point was performed by Wimbish, McDonald, and LeBlanc in some capacity. According to LeBlanc, it was Sylvia Robinson who was most in touch with what was happening in the clubs; alongside arranger and producer Clifton “Jiggs” Chase, she would play a role that was as curatorial as anyone in the band, bringing up ideas that she’d gleaned from hip-hop DJs of the time (Flash was a frequent contributor) and having the band adopt those ideas for the bulk of the label’s output: “That’s the Joint,” “Funk You Up,” “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” etc. (From Tackhead, only guitarist Skip McDonald played on “The Message”—Duke Bootee produced that song himself, after being tutored on the drum machine by LeBlanc and Jiggs Chase.)

If their time at Sugar Hill was an especially rigorous training ground for their future career it also was foundational for an entire genre. It also pointed to the nascent conservatism of hip-hop’s shift from culture to business; a funk/disco band replaying records DJs were innovating with in the clubs surely had an outsized impact for being the very earliest vanguard of hip-hop as recorded art. But their choices in the Robinson era that helped export a sound globally. The radical new approach of the hip-hop aesthetic that was coming to the fore in the early ‘80s—minimalist, driven by producers like Pumpkin, Larry Smith, Davy DMX, and marketed as hip-hop’s future via Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons—redefined rap as having a sound of its own, and that sound was really the sound of technology and the energy of the future. Facing that, the members of Tackhead embraced it.

“All the other bands hated us,” LeBlanc said in a recent interview. With one exception. “They despised us, all except for Parliament-Funkadelic. They liked us. I think George Clinton knew what rap was going to do long before we did, because to me, it was just a progression of funk music.”

LeBlanc first recognized his time as a session drummer was limited when he heard The System’s bleeding-edge “You Are In My System,” and saw the crowd’s reaction. Drum machines became his future. Flat-broke, having just left Sugar Hill after spotty payment history, with $50 invested by record exec Marshall Chess (son of Leonard Chess, founder of Chess Records) and a few spoken word records “donated” by the Sugar Hill studios library, LeBlanc recorded “No Sell Out” using tape edits of Malcolm X’s voice and a drum machine.

“No Sell Out” was blackballed domestically by Joe Robinson of Sugar Hill, upset that LeBlanc had brought the record to Tommy Boy. LeBlanc had done so specifically because he knew, he says, that Robinson would never have shared the royalties with Malcolm’s widow Betty Shabazz. LeBlanc received permission from Shabazz to release the track, at a time when Malcolm X’s name and legacy had become shrouded in an aura of conspiracy and antiblackness, a fog emanating from his violent killing. The song, with its use of vocal samples, anticipated what would become a dominant aesthetic technique in industrial and hip-hop.

“No Sell Out” also drew the attention of UK dub and experimental music producer Adrian Sherwood, who became Tackhead’s fourth member as an engineer—an engineer who also worked with the band in live settings, triggering live effects and helping the group cultivate a sound incorporating dub’s innovative palette of unrehearsed microsyncopations.

The band’s early forays into industrial music included collaborating with Mark Stewart on 1985’s As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade, an explicit lean towards agit-prop which would deeply inspire Trent Reznor. (LeBlanc would later admit that even as he produced and engineered Reznor’s debut, he considered him a kind of knock-off Mark Stewart at the time—going so far as to take the upfront cash rather than a royalty from the NIN frontman, not anticipating his album’s success).

The sound of the band became hugely imitated. On Tackhead’s first Stateside tour, in ‘86 or ‘87, they were booked at a club and told Prince would be in attendance. They performed for a near-empty room. During the concert, LeBlanc’s monitor was suddenly cut. He reached for his headphones, and the monitor cut back on suddenly. Then it happened again, and again—“about five times in a row,” LeBlanc would later claim. The last time, a disembodied voice came from nowhere— “What’s the matter—can’t you keep time??” “I didn’t even know it but I think I was auditioning for Prince,” LeBlanc would later recount. “After Prince died, I saw a picture of his house. And that was the place we played.” (One clear inspiration to Prince was LeBlanc’s “Kill the Devil.” Prince’s suspiciously-similar “The Future” appeared on the Batman soundtrack.)

The best Tackhead full-length—the only one that matters, at least in LP form—is also the first entry in our Cyberfunk Album Canon. Released in 1986, Major Malfunction is a concept album about the Challenger explosion that killed all seven crew members in January of that year, midway through recording. It was constructed through tape edits and mixed by Sherwood, but LeBlanc’s own description of the project as a blend of “music concrete, dub, rock, hip-hop, and more” tends to undersell what makes it great—as if it were a mere synthesis instead of a cross-cultural common denominator. (When Future Sound of London visited LeBlanc in the studio hoping to figure out what mysterious technological methods he used to construct the thing, they were disappointed to find out it was edited together simply, with old-fashioned tape-edits of a Fairlight sampler, an Oberheim DMX drum machine, an AMS Delay, drums, guitar, and bass.)1 Its samples of Margaret Thatcher, William S. Burroughs, and Ronald Reagan woven with its abrasive, percussion-forward drum machine sound seems positively future-primative, especially when compared with other acts’ sophisticated, glossy use of the new technology. This was the sound of steel striking stone.

“Move” is the platonic cyberfunk ideal, a propulsive mid-’80s masterpiece with keyboards performed by Ministry’s Al Jourgensen (credited to “Dog”):

In part, Major Malfunction came from the sessions for Ministry’s Twitch—records Jourgensen had passed on. (He famously copied many of Sherwood’s studio settings so he could replicate Sherwood’s sound—but more on Ministry later.) Ministry had come to work with Tackhead through Sherwood. In Chicago, Ministry’s label Wax Trax had recently spun out of a popular record shop of the same name. An imported record by UK band African Head Charge (likely 1983’s Drastic Season), engineered by Sherwood, had become a regional favorite in the midwest thanks to the Wax Trax store. Through his label, it inspired Jourgensen to seek out Sherwood to work on Twitch. (You can follow the insane creative byways of this era in this thoroughly sourced blog post.)

Other highlights of the album include Skip McDonald’s atmospheric work on “Object - Subject,” another deep ‘80s vibe with screaming guitars, and “Technology Works,” an ironically-titled staggering LeBlanc groove whose concept remains as relevant today. (Most Tackhead records feel wildly contemporary in concept, with a few exceptions, like the nonetheless charming “Rockchester” (it’s about the celebrity culture of magazines, an ancient sort of written TikTok) and “What’s My Mission Now?,” a song about profligate military spending that nonetheless seems less radical than fiscally responsible.) But more than its content, the music Tackhead recorded in this period, its pessimism and brutalist aggression have a timelessness in part because they feel as if they exist outside the quaint slickness of contemporary retrofittings of ‘80s melodicism. Funk, technology—those were the future, the present, and the past.

I’m really digging your maniacal scholarship in these posts!