CYBERFUNK is a metagenre pastiche conceived to capture the lost or diminished aesthetic vocabulary of the mid-1980s. The best way to understand the laws and byways of CYBERFUNK is to pre-order Time to Make the World End, Vol III, a CD-only mix which explores the network of mainly obscure gestures which make up the sound. You can read more about it here, read a Q&A with ISIL CEO on the DJ Mix’s origins here, or explore ten cyberfunk hits you already know here.

But why read about it when you can experience it firsthand? Pre-order the mix at ISIL.CLUB. Orders ship by end of year; US only, for now. CD only, forever!

Unlike Larry Smith, Bill Laswell was not a generational talent-coach or pop craftsman; unlike Tackhead, whose innovations forged a series of cross-genre creative blueprints, Laswell’s genre-synthesis was spontaneous and social, occasionally brilliant, and as often, pointless—a roll of the dice. No artist better embodies the nexus of time, place, people, style, and influence of CYBERFUNK—while somehow still not quite “getting it”—like Bill Laswell.

What does it mean that such a theoretically emblematic figure could capture every characteristic of the CYBERFUNK ETHOS while somehow evading its fundamental essence? An artist for whom the sum is less than the parts, or perhaps the parts are what he really enjoys; the Forest Gump of the American musical ‘80s was wrapped in the fabric of his time so completely he seems incapable of failure, coasting along the currents of history and strategic networking towards an end only he could design…I want to say from the beginning, I have nothing but love and respect for Bill Laswell, a prolific legend of whom I think it’s higher praise to suggest he ultimately made a lot of great music, rather than read a laundry list of famous people he’s worked with, as most biographies will no doubt begin. “This guy had Miles Davis’ phone number!” Ahh but what did he do with it….

In the spirit of helping our fellow man, in fact, I’d like to link to a (still very active) kickstarter for Bill Laswell, who has been struggling the last few years from serious health conditions which have kept him from working as a musician. Contribute here! I am first and foremost a Bill Laswell Fan, endeared and nonplussed by his survivalist unpredictability in equal measure….that ambiguity is like a magic eye, requiring an amount of focus on the catalog before shapes are discerned within its endless surfaces…luckily we’ve done the work for you…

“What did he do with Miles Davis’ phone number” is the confounding factor in the Bill Laswell phenomenon—he made a lot of stuff and a lot of it isn’t so much Bad as I Don’t Remember It Five Minutes Later. He’s a bass player, a networker, a cosmopolitan appreciator of many different genres and sounds, but his methodology would be better described as “random” than strategic. An agglomeration of what we might today call Prestige, a cultivated aura of connectedness, of inspiring FOMO in other artists. Looking deeper, a theory: Perhaps a performer’s faith-based belief in the “magic of the moment” that, at a crucial level, abandons critical faculties in favor of a near-religious reverence for the unknowable alchemy at the heart of everyday creative interaction.

This deference to pre-critical serendipity, to randomness is a valuable method of producing prolific creative work—an essential one. Yet at some point curation, the ability to edit, enters the frame. Maybe editing is an indulgence of the privileged (certainly it is now, for writers), and Laswell is def more of a gigging journeyman. Yet if your approach to creation is about playing the odds—hoping something brilliant comes out & then releasing it either way—you have to know that the house always wins—that just because you put together an album with Archie Shepp, Whitney Houston, and Brian Eno (and Nile Rodgers! and Tony Thompson! and Nona Hendryx! and and and) doesn’t mean that you’ve rolled lucky 7 on 9 tracks straight… indeed, his group Material’s 1982 Celluloid album One Down, which literally features the recording debut of one Whitney Houston with an Archie Shepp solo on “Memories” among other theoretically fascinating collaborations, is not that good. It has a kind of aimless inertia (this is my impressionistic music writer description) or lacks great songs (my A&R description). (Some love “Busting Out,” which was a big dance hit at the time. YMMV.)

The AllMusic Guide review of One Down suggests a tempting rationalization for the album’s lack of laurels: “Sure, it sounds dated but that doesn't make it less attractive.” Here we have a three-card-monte effort at obscuring the causal relationship between “not making good songs” and an album’s ambivalent reception; it must be the dated aesthetics that have kept this gem from the public eye! I would suggest to anyone who is struggling to find a foothold in the catalogs of Cyberfunk legends, of early-to-late ‘80s drum machine music, that the problem is a lack of narrative and critical focus rather than some sort of intrinsic patina of “dated” production. The sound hasn’t been narrativized in a very compelling way since the mid-80s—but lets build that new story from exciting music, not by peddling an association with specific prestigious brand names or the presumptuous suspicion that letting your Ninja Turtles play with your GI Joes will necessarily spark something meaningful.1

This is evidence my animating interest in CYBERFUNK is a balance between these novel sensuous surfaces and an unusually fertile creative terrain, AKA a huge number of forgotten Great Songs—NOT those surface aesthetics in isolation. If anything, those surfaces are familiar to everyone already, and without a viable universe of incredible music this project would not be so fulfilling. Our collective assumptions about taste, about “dated” sounds, have effectively minimized a wide swath of great art, which has in turn effectively obscured a bunch of great music. None of which appears on Material’s One Down.

Fear not, listener. I have begun—and I hope others will continue—the project of exploring some of Bill Laswell’s best Cyberfunk anthems. Here are a few areas to explore, and as a bonus, some non-Cyberfunk Bill Laswell projects I would recommend unreservedly.

BILL LASWELL-ERA HERBIE HANCOCK

As I’ve mentioned before I have some ambivalence about Herbie Hancock’s music in this period, and it’s mainly reflective of my ambivalence about Laswell’s work in general. I don’t think it’s quite as rewarding as Miles Davis’ mid-80s work from the time, in terms of its ability to do something with these new technologies. (More about ‘80s Miles in future posts). Future Shock, Herbie’s first Cyberfunk release, is in large part a collaboration with Material, including Michael Beinhorn who was all over One Down.

“Rockit” is of course “the classic,” created when Laswell asked Afrika Bambaataa to recommend a DJ; Bambaataa suggested Whiz Kid (who we discussed in the last post) but he was out of town; he also recommended DST, who was available. DST and Laswell put the track together in LA and, according to Laswell, Hancock recorded his part in 5 minutes. It was a freak hit that captured the emerging mechanistic sounds of the time, Hancock’s admirable embrace of futurism. My favorite song off Future Shock however is “Autodrive,” which also has an amazing video:

DEADLINE’s DOWN BY LAW: THE BEST LASWELL CYBERFUNK LP

In the 1980s, “down by law” was one of the coolest things you could be—two years before MC Shan released Down By Law, and one before Jim Jarmusch released a film of the same name (but two years after Duke Bootee said it on Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “New York New York”), a new Laswell-co-helmed group called Deadline released Down By Law, which is easily the best Cyberfunk full-length ever released by Bill Laswell, as far as I’m aware. The only knock against it is that nothing on it is as good as its best song, the 11-minute-masterpiece “Makossa Rock”:“Makossa Rock” features the harmonica of Paul Butterfield of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the trumpet of Olu Dara (Nas’ dad, obviously), the bass of Jaco Pastorius, and jazz Trombonist Steve Turre playing the didjeridoo (he plays conch shells elsewhere on the album)—if I knew this song in high school it would have blown my mind, though equally likely I would have dismissed it as “dated,” lol. Butterfield is flown in from my dad’s tape collection, Nas’ dad from bits of accumulated knowledge about the rappers I was into, and Jaco was every high school jazz combo’s dream collaborator (Steve Turre I very distinctly recall covering jazz magazines)—how were they all together on one record? Well, that’s the central gimmick of the Bill Laswell formula isn’t it!

What happened on 1985’s Down By Law that was missing on 1982’s One Down?One might argue it’s Manu Dibango, who is an animating presence on several tracks; Dibango’s Laswell-produced Electric Africa, released the same year, is worth checking out and also features Senegalese percussionist Aiyb Dieng, as Down By Law does. For my money, though, Electric Africa lacks a “certain something”.

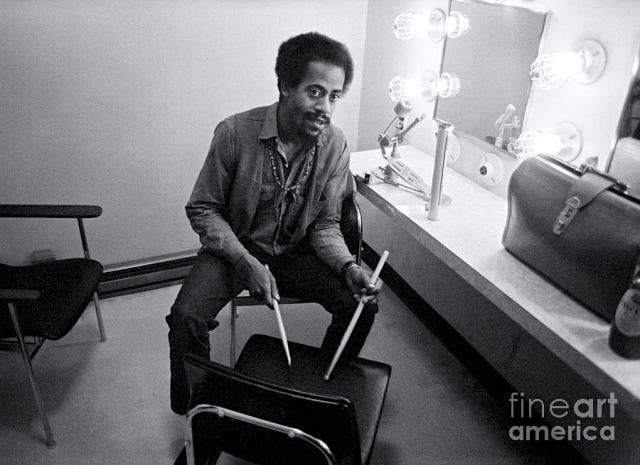

Another theory might start with Phillip Wilson.

Wilson was a percussionist who started out playing drums for Rufus Thomas and Solomon Burke. Burke once left Wilson and the rest of his band stranded, prompting Wilson’s first career shift.2 His story as a musician is as densely packed with Forest Gump-like moments as Laswell. After Burke, he played in Vegas; then in Watts, during the Watts riots. Then Phoenix, Arizona. Then Detroit, where he worked for Motown (though not on recording sessions—just live gigs) including backing Marvin Gaye. After a brief spell in his St. Louis hometown, his friend Lester Bowie called him to Chicago, where Wilson became a founding member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago.

In Chicago, they played a concert where he and Allen Ginsberg pied each other; he played with the MC5 in the late ‘60s. (The MC5’s manager, John Sinclair, may have been a formative influence on Laswell’s musical philosophy, hiring acts like Archie Shepp or Miles Davis as openers for the proto-punk group). Wilson started playing with blues acts in Chicago—Otis Rush, Magic Sam, and Howlin’ Wolf. “Howlin’ Wolf was my favorite, but I didn’t stay with him long – he was a dangerous person to work with. You did not mess up. But I enjoyed that period very much. I learned a lot about playing the blues, I saw how different it was from playing rock and roll, and other things.” Around this time, he joined the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and began touring nationally. In 1968, he played alongside Jimi Hendrix.

In 1972, he was the drummer for Julius Hemphill’s album Dogon A.D., which the New York Times called one of jazz’s 100 essential albums. He started his own band Full Moon in the early 70s; gigged for Stax Records in the late ‘70s, writing Isaac Hayes demos. While working at Stax at the time the company was falling apart, he spent time in Mississippi and Arkansas, listening to jug band music, and played in a Country&Western band. Then he got a call from Anthony Braxton, and ended up in the New York loft scene of the 1980s playing forward-thinking avant jazz. During this entire period, he was still recording with Lester Bowie and the Art Ensemble of Chicago. He also recorded with Laswell, of course, and the Last Poets. In 1992, Phillip Wilson was senselessly killed by a stalker. His killer was caught thanks to America’s Most Wanted. In 1997, Marvin Slater was convicted to 33 and 1/3rd years.Down By Law is as much a collaboration between Wilson and Laswell as it is a Laswell album outright. Wilson plays a wide variety of percussion on every track, including a Balafon and an Mbira. These are combined with DMX drum machine beats (same one used in so much of the greatest Cyberfunk of the era) credited to both to Laswell and Wilson. It is fair to assume that Wilson may have been as much the creative force behind the project as Laswell. The other noteworthy thing is that on “Makossa Rock” in particular, Laswell is not the bassist, replaced by Jaco Pastorius. I don’t want to say this album is good because Laswell is “less involved”—it still feels very much like a vanguard ‘80s technology-oriented Laswell-type-project. But it does feel like the intersection of talents here were a bit less “nuts and gum, together at last!” than earlier efforts.

Finally, I think there might be something of what I described in Rick Rubin’s “Dust Cloud”, where Laswell’s amateur focus on the DMX—ultimately, a democratizing force for the drummer’s role—works well in conjunction with a professional percussionist, by operating at a remove from normal drummer rules. A bassist and musician, true, but a percussion naif experimenting with new technology who has clearly been drawn to its novel and future-shock possibilities, focused on that aspect of creation, is liable to be working to his strengths, at a time when the rules don’t matter as much as how you break them.MATERIAL IS NOT IRREDEEMABLE — IN FACT THEY HAVE SOME AMAZING MUSIC WITH A HIP HOP CYBERFUNK PIONEER

Material’s 1989 album Seven Souls is one of my favorite Laswell releases, and a large part of this is due to his William S. Burroughs collaboration “Seven Souls,” featured prominently in The Sopranos, in which Burroughs reads from his novel The Western Lands. One of the all-time sickest prestige TV soundtrack moments on a show full of them. The bass is going crazy on that one, too—Laswell just crushing it.

However, the album’s most-Cyberfunk song is “Equation,” a feature for Rammellzee, a favorite of mine and well worth surfacing for your own Cyberfunk DJ mix or future edit.SOME BILL LASWELL CLASSICS WHICH ARE NOT CYBERFUNK BUT I KNOW TO RULE ASS

First off, I would love for readers who are Laswell fans to contribute your own suggestions in the comments—his discography is vast!

These are outside the remit of CYBERFUNK but I can’t recommend enough. It goes without saying that Brian Eno and David Byrne’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts LP rips and Laswell is essential on his contribution to “America is Waiting.” The story goes that a random early ‘80s gig for Deadline, with Wilson playing drums, ended up getting a rave review from the New York Times’ John Rockwell. Eno had brushed off Laswell every time he’d run into him until the review ran. “He would say, “Ok, let me think about it,” or “We’ll talk about it,” or whatever. But then he saw that review, and that changed everything. He said, “I have a session tomorrow at 12 Street. You should come, and we’ll record.” That’s all because of Rockwell’s article.”3

Sonny Sharrock’s Ask the Ages recently got a great Pitchfork review from Andy Cush and I couldn’t agree more, this album rocks.

And finally, probably my favorite overall Laswell release was recommended to me some time back by Classixx’s Michael David and has stayed in rotation since. I know I have sounded “down on” Laswell at times in this post, but I should be clear that I think he’s actually a legit legend with a wide and thorough skill set. When it comes to his skills as a producer, friends have recommended his work remixing Bob Marley, on his dub album Dreams of Freedom. But I don’t think he’s done a better project than Illuminated Audio, a remix album of his wife Gigi’s debut project. I can listen to this thing over & over and never really tire of it, I think it’s easy to imagine a narrative of devotion to this but I’d rather let you check it out & figure out your own extra-textural associations.CYBERFUNK is a metagenre pastiche conceived to capture the lost or diminished aesthetic vocabulary of the mid-1980s. The best way to understand the laws and byways of CYBERFUNK is to pre-order Time to Make the World End, Vol III, a CD-only mix which explores the network of mainly obscure gestures which make up the sound. You can read more about it here, read a Q&A with ISIL CEO on the DJ Mix’s origins here, or explore ten cyberfunk hits you already know here.

But why read about it when you can experience it firsthand? Pre-order the mix at ISIL.CLUB. Orders ship by end of year; US only, for now. CD only, forever!

From the preamble to an interview with Laswell: “Laswell works without a playbook. He's driven primarily by instinct. And if that instinct calls for fusing rock with turntablism, tablas with reggae, ambience with noise, jazz with Moroccan trance music, or all of the above, so be it.”

Much of this information on Wilson is culled from this interview, worth reading in full! https://www.furious.com/perfect/phillipwilson.html

This is very helpful, because I’ve been frustrated with the results of my numerous attempts to find recordings involving Laswell that help me understand why everybody wanted to work with him.

The New York Gong album with Daevid Allen, which is a pretty good take on punk!